I left college without a degree and loads of student-loan debt. And yet…

I’m regularly reminded of the years I spent in college.

It isn’t an old photo, or a Facebook post or a text from a former classmate that stokes flashbacks of the best years of my life.

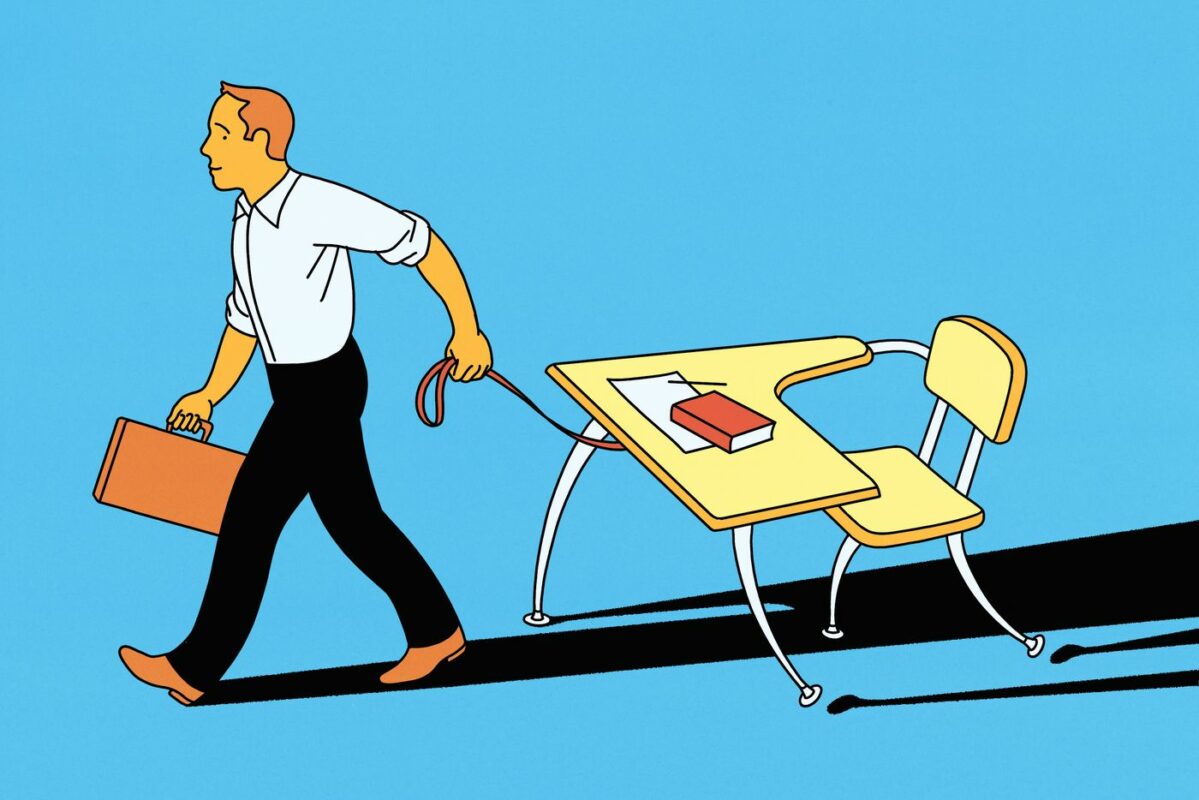

What jogs my memory is the monthly $500 withdrawal from my bank account to pay off my student loans.

If anybody should question the value of college—as so many young people do these days—it should be me. I attended college for six years, took on more than $60,000 in debt, and left several credits short of a degree. None of the courses I took in college have anything remotely to do with my current job—as a Wall Street Journal editor whose assignment is to help readers find our journalism on search engines.

And yet, I can also say that without college, I wouldn’t be here today.

First-generation student

I started thinking about all this recently as I watched an old home movie. It was a Christmas gathering sometime in the mid-’90s—four generations of adults celebrating all that life had given them. And it struck me: Nobody on my screen had a four-year college degree. There were two military veterans, a retired hat seller, an insurance agent and a couple of 20-somethings who, at the time, only had high-school diplomas. My father was barely literate and eked through high school by playing sports.

They were the backbone of America; blue-collar workers who owned their homes, drove American cars and somehow raised children in safe, welcoming neighborhoods. None of them had a college degree (or student debt). But the world was changing. They knew, especially my grandmother, that having an education led to a better life.

Now, 30 years later, I’m in my mid-30s and living in New York City, working in a white-collar job. So as I watched that movie, I couldn’t help but ask myself: What role, if any, did college play in that?

Souring on college

Clearly, I’m not the only one asking that question. On the one hand, the benefits of higher education are apparent. College graduates typically make more money, have lower unemployment, vote at higher rates and even live longer, healthier lives.

But despite the overwhelming positive outcomes, Americans are souring on the value of college. It shouldn’t come as a surprise that when you type the phrase “is college” into Google, it autocompletes with the question, “Is college worth it?”

Many college grads find themselves underemployed, earning less and spending more on student-loan payments, than their parents. They also tend to delay major life events such as getting married, having children and buying homes.

“It was a belief system passed onto young people that no matter the cost of college, your quality of life was going to be so much better. It was this salvation story that the investment was going to be worth it,” says Nicole Webb, senior vice president at Wealth Enhancement Group.

Growing up in the 1990s and early 2000s, I bought into that dream, and my teachers made college seem like a foregone conclusion.

I enrolled in a small community college right after high school, then transferred to a state school the following semester because that’s what everybody told me to do.

I often worked two jobs during school to help pay my bills. I waited tables, tended bar, parked cars, sold vinyl records and wrote for a local music magazine. I can still recite how many ounces of bourbon are in a mint julep. It’s 2.5.

Eventually, though, the financial burden became too great, and I quit with tens of thousands of dollars in student-loan debt and without a degree. I felt I had no choice: I had maxed out my federal student-loan allowance just before my final semester.

So how can I think all that was worth it?

The real lessons

The lessons I learned in college were more interpersonal than they were academic. As a first-generation college student from a small town, college was my first experience mingling with people from different backgrounds than mine: a son of Romanian immigrants, a wheelchair-using poetry professor whose wife cut his hair in the Cuyahoga River, a free-spirited daughter of an emergency-room doctor.

I learned how to get along with people who saw the world through a different lens than I did. I learned firsthand the consequences of missing class, being late or blowing off an assignment. It took a while for me to learn discipline. It also took me a while to learn how to speak “college,” meaning the elevated, professional language that’s common in white-collar workplaces.

I didn’t retain much of what my professors tried teaching me, to be honest. What I did learn, however, was focused curiosity, how to defend an argument and the art of knowing when to take creative risks. I also learned how to mine for information and, most important, how to teach myself.

All of it was humbling—and the best preparation I could have gotten for succeeding in a world that was changing faster than ever.

I may not have understood it at the time, but quitting college wasn’t the end of my learning. It was the beginning. Because to keep up in a competitive industry, I needed to continue building my toolset.

I tried finishing my degree remotely during the pandemic. I took one look at the out-of-state tuition costs combined with the additional classes I needed and changed my mind. At that time I was already years into my career. Did I really have much to gain by getting that piece of paper now? I don’t think so.

But how about this for a twist: I recently began teaching a class remotely for a state university.

In the end, do I regret going to college? Absolutely not, even though I would have done things differently. There are many ways to achieve success in today’s world. Some of my oldest friends who never finished school went on to be successful in their fields. For me, however, college is what I needed to give me a push, and to teach me the life skills I needed to grow and learn.

And if I ever doubt my decisions, if I ever wonder whether those student-loan payments that haunt me every month are worth it, I think of my grandmother. She always wanted to go to college to become an archaeologist or a journalist, but never had the chance.

One of her final gifts to me before dying was a sweatshirt with Columbia University, my dream school, blazoned across the front. I never had the grades, the extracurriculars or talent to make it into an Ivy League school. But the name on the sweatshirt wasn’t what was important. Rather it was what the sweatshirt represented—that I could be the first of my family to go to college, and to take advantage of what an education offers.

I still remember the painful moment when I realized that I left that sweatshirt behind during move-out day from my state-school dorm. But I now understand that what I left behind on that college campus isn’t important. What’s important is what I took.

Will Flannigan is an editor for The Wall Street Journal in New York. He can be reached at [email protected].